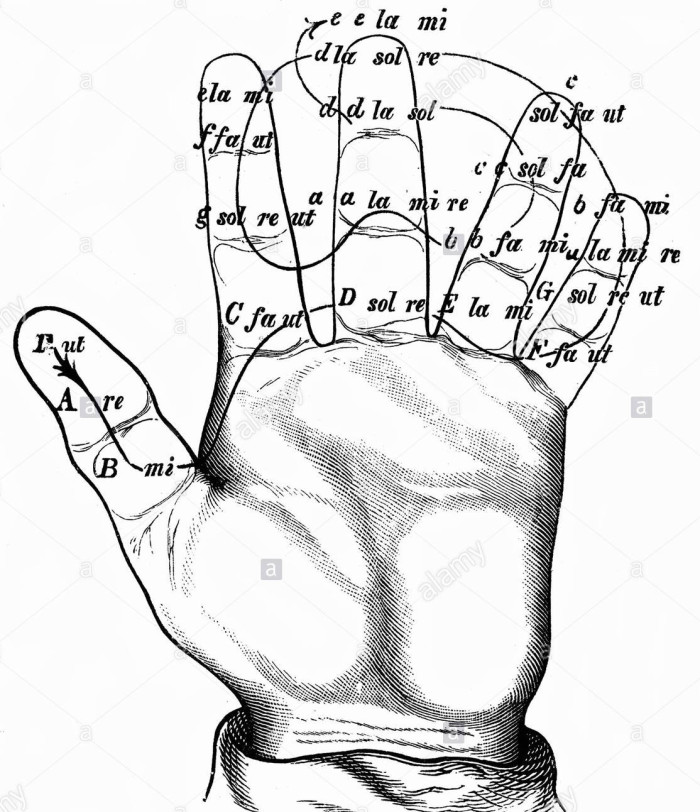

(Feature photo: “The Guidonian Hand,” a mnemonic device to aid the learning of sight singing; a precursor of Tonic Sol-fa; devised by the Guido di Arezzo.)

In response to The New York Times article “650 Prompts for Narrative and Personal Writing.”

403. “What Would You Like To Have Memorized?”

Seneca wrote once about how grown men ought to avoid the childhood habit of memorizing another person’s thoughts. He said it’s fine to know a few poems by heart, some lines of the Odyssey for example, but to dedicate time to memorizing other men’s ideas, only to later regurgitate them, is a waste. Instead we should cultivate our own thoughts, use study time to analyze the ideas of others, not merely commit them to memory. I almost copied Seneca’s words into a notebook, but figured I’d be better off internalizing the gist: now I can only paraphrase it, but at least this way I stay true to the heart of the message, and bring it into my own lexicon: to remind myself I don’t need to memorize everything endlessly.

My translation seminar professor, Val Vinokur, writes, “at least in the Russian context, God is less dead than constantly and necessarily forgotten. In such a context, ‘God’ is basically a mnemonic device for responsibility and for the suspension of the all-negating rational ego.” He goes on to cite the “atheist in a foxhole” bit, to shine light on the saying’s truth. In Tolstoy for example, Levin finds peace in mowing the grass when he stops thinking about it and simply mows. Yet he seeks God when things go bad for Kitty, or for his brother Nikolai. Levin, a non-believer, prays when things go bad. But what about the ending? (I think) He realizes that if there is no God, he stays the same. And if there is a God, he was always part and parcel with God. There being a God (or not) doesn’t affect him, though the concept of God works to keep him happy in another sense: When you are doing the right thing, being yourself, you don’t need to think, and certainly not about “God.”

Which reminds me of a Peralta Ramos line: “A Dios hay que dejarlo tranquilo.”

Which, of course I’ve memorized. Which, as you might know, is pinned to the wall next to my notebooks, along with William Blake’s Tiger Tiger poem, which I’ve also memorized.

Tiger Tiger burning bright

in the forest of the night

what immortal hand or eye

could frame thy fearful symmetry?

For a time I had in my head the lines, but not the poet’s name, as in I had forgotten his name. Ah, names would be fun to memorize, all of them, if I could remember everyone’s names. I try. I try.

I watched this video once about elephants and their memory. Apparently elephants are highly evolved. We know they cry, that they have emotions and mourn their dead. But the video showed them also recognizing humans after decades of being apart, of remembering where the right watering holes are in the wild. And all this, we can assume, helped the elephant evolve into the magnificent beast that it is, yadi-yadi. But! What’s most interesting about the video is the connection it draws between the animal’s refined emotion and its capacity to remember. To remember is to feel. Feel and you shall remember.

Which reminds me of a comedian’s bit about how women are much better at remembering the details of a fight with a man than the man. It’s because they will associate the things men say with emotions; they will incorporate facts into the microcosm of their minds, fitting details upon details upon details upon details, weaving together a vibrant narrative.

I know, personally, that when I learn something new, I have a higher chance of remembering it if I connect the new information with preexisting information. When I found out my nurse’s name was Martina, I recalled my cousin Martina and how she studied pre-med. Connection made. Whenever I greet this nurse, I greet her by her first name. When I teach a new word to my students, I try to tell them a story that will connect the new word with their emotional core (the deeper the better). The word “crowded” came up in a reading, for example. “What does this mean, teacher?” Instead of giving them the translation, or the dictionary definition, I asked the students to imagine riding a subway, and mimed being in a crowded subway. “When you rode the subway this morning, to get to class, were your arms up like this and your face like this and the people around you like this?” “Yes, teacher.” “And how did you feel?” “Annoyed, teacher.” “Now look around you: this room can have 25 students, and when we have 25 students, how does it feel?” “Ohhh.” “It feels CROWDED.” “Ohhh.” “Repeat after me, CROWDED!” Something like that.

Needless to say, memorizing does come in handy. But it’s probably better to intuit the world around us, let it pass, and continue without holding it in. Holding in is like memorizing. Letting go is better. What does that even mean? I don’t know. But try holding your breath. No. Really. Take in a deep breath, and hold it. Hold it. Hold it.

How does that feel?

(The “holding in your breath” concept I borrowed from Watts; there’s simply too many good ideas for the picking. Like just yesterday a book seller explained his traveling bookstore concept: “Somos Sancho Panza con libros”; I laughed so hard I had to remember the line.)