Circumscribe, v.

1. restrict something within limits.

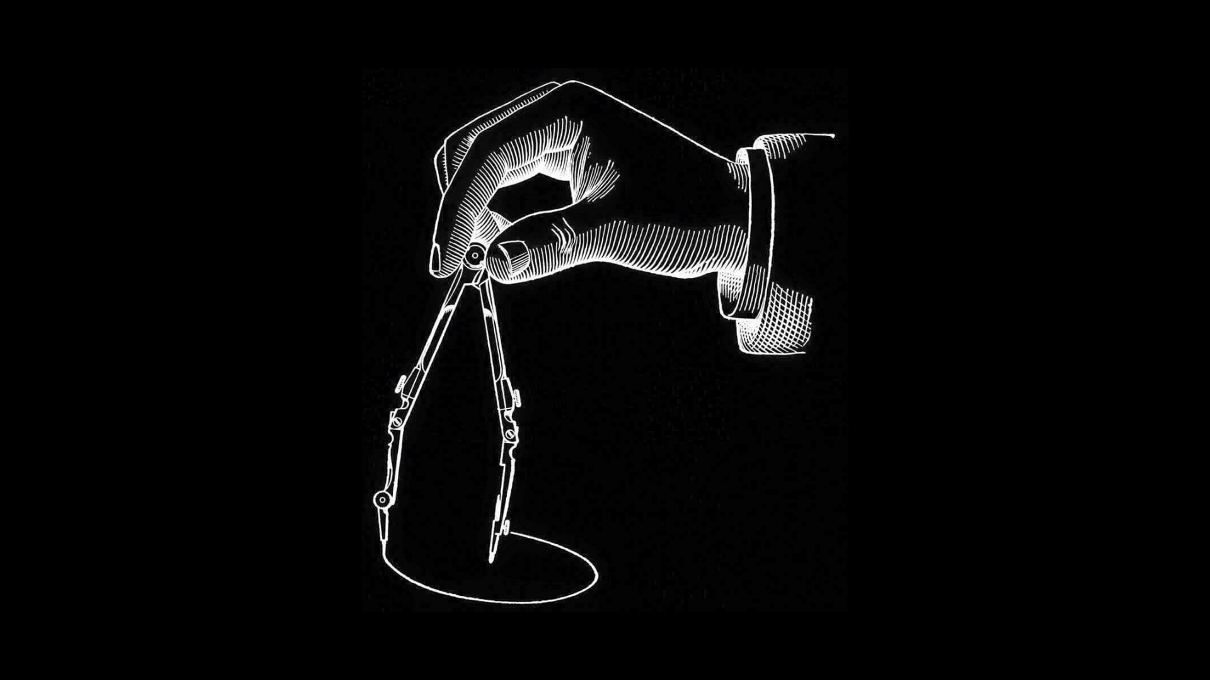

2. [geometry] draw a figure round another, touching it at points but not cutting it.

Origin: Latin circum “around” + scribere “to write”

I.

Just as the word describe comes from the Latin “to write down,” let us reconsider a similar word, largely ignored from math class, to create a greater, more vigorous literary term. The word is circumscribe, and it comes from the Latin “to write around.” If it sounds familiar, that’s because many writers exercise it already — a handful on purpose, but most on accident.

To describe something means to put it down on paper. It’s a pretty neat trick in and of itself, used to enrich a story, bring details to life, or otherwise inflame the reader’s imagination. For example, let’s say we wanted to open a scene, so we write: “He grinned as he pocketed the coin.” In one confident stroke, two things get described: a character’s facial movement, and his clear action on a direct object. For comparison, consider a shakier use of description: “He showed satisfaction as he took possession of his well-earned reward.”

Clearly the second, more verbose sentence is weaker. But why? Whether it’s needless words or needless details, when describing, remember: less is more. (Note: both sentences come from the Elements of Style, in the section devoted to the power of concrete language.)

Or recall the old Miles Davis adage: “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play.” What attracts us to a sentence isn’t just what gets described, it’s also what doesn’t get described: the type of coin (gold, silver, a quarter, a half-dollar), any secondary actions (standing, sitting, breathing), or who “he” is. Not only do carefully crafted details keep a sentence lean, but omitting them teases us to find out more.

Yet, that’s not all. Subconsciously, a brilliant thing happens to the reader with an above average lust for words. When she strings these eight words together, or graces any powerful opener with her full attention, something more mysterious than simple omission. Well, it’s no mystery to those who “read between the lines.” And that’s because from description blooms circumscription.

Now, I just gave it to you straight, even underlined the damn thing for you. How often are my thesis statements so easily surrendered? Rarely.

Nonetheless, being a fanatic of the expression, “Easy come, easy go,” I want to offer a more visceral experience of this literary term, by touching around it at points. If successful, may the Oxford Reference of Literary Terms amend the following error:

There are no results for 0 entries for:

II.

Consider the sentence again, “He grinned as he pocketed the coin,” however, this time don’t pay attention to the text. Instead, imagine the author of the sentence drawing four lines, to compose a square on a canvas. Viewed this way, you visualize not only a figure, but simultaneously the area inside the lines, as well as the area outside.

The negative space is anything outside the square on the canvas, meaning anything ignored by the sentence. Examples include, again, the kind of man, the type of coin; but also the weather, what he ate for breakfast, the year. These details may or may not become relevant as the story unfolds in subsequent lines drawn by the author, which will contain other parts of the canvas. (Let it be said that a master work utilizes 100% of its canvas, the same way a great novel needs 100% of its words.)

Focusing on the original sentence, the perimeter our eyes are tracing, “He grinned as he pocketed the coin,” description can engage us. We might even grin in neurological echo to picturing the scene, eager for the next line to engage with. The most eager among us, upon rereading the sentence, may even begin to wonder: Why is the gentleman grinning? Clearly assuming that the man is a gentleman, when maybe he’s a crook.

At any rate, the more we appreciate the sentence, the more a center area appears. And there it emerges, the figure’s positive space: the square’s shape, the thing being circumscribed by the author, intentionally or not, as it becomes the theme of the sentence the reader intuits. In other words, when the writer writes or the reader reads those eight words there appears a very, very clear picture of greed, without ever using the word.

This is only a guess, an intuition. But one that springs from within the eight words forming that positive space. If ever there were a tonic against the Authorial Intent debate, which values the biography surrounding a work of art above the theme that art encompasses, it is this: to acknowledge the power of circumscription. A side benefit, to be sure. (Another side benefit: with circumscription, more is more!)

Whereas the central benefit to appreciating the power of circumscription is to deepen our appreciation of storytelling, for both author and reader.

Following his opener, the author might craft a second sentence to deliver backstory on “he”; or might hold our attention at the emphatic end instead, keeping on eye on the coin. Either way, by grasping negative and positive space, the author will write any number of subsequent sentences — drawing any number of shapes — consciously selecting the most important detail, to naturally continue circumscribing his main idea.

Meanwhile the reader, watching figure upon figure, shape around shape, will engage with a really nice story — visualized as a series of concentric circles, or a fictional archery target. At once pretty and mesmerizing, this target leads the reader of keen sight and steady grip to shoot right where the author wanted her to, dead at the bullseye. (The opposite case, let it be said, should be avoided: slapping together elements in a story, without care, resulting in a flat image of poorly drawn shapes, not a single entry point on the canvas to guide the reader to ecstasy.)

III.

I didn’t hop on my keyboard today to steer the course of one word away from its possible obscurity toward a brighter literary future. It’s just that when I started to write about what I really wanted to write about I couldn’t strike directly at the topic. It evaded me, or at least worried me, since I absolutely had to do it justice. Thus, I wrote Parts I and II like a frame, for context, also throat clearing.

But mostly, ladies and gentlemen, yes, I and II are a frame. Yet another different literary device! Which might as well be called a filter, since I hope it filtered any riffraff from reading the personal story below, wherein I bare my heart openly.

In a way, I also thought it would be more emotionally rewarding to “write around” my topic, as opposed to diving right in. A friend of mine years ago had called it a writing exercise, while my workshop professor once explained that this was how modernists wrote (“Iceberging,” “circling,” or “steaming”). So, when I clicked “Add New Post,” and a familiar terror gripped me, I switched tabs on the browser, watched YouTube instead. But then, pushed by guilt, pulled by inspiration, I felt the wind of a new idea rise, howling to give active circumscription a shot. Suddenly the rough waters of my excuses subsided. And I drew sails.

After all, what better motivation for using a literary device is there, than to put words the page, or keep our imagination moving.

Here it is, the emotional story, as promised. It answers a question my wife asked me the other day: “Who was the man who had the greatest impact on your life?” There was an obvious answer, but I chose the less obvious one instead. Can you guess who?

The Man On the Pier Watching Me

Years after my boat had capsized, he turned my world right-side up when he told me why we mattered. We were sitting by the pool at my aunt’s house, listening to him say he didn’t fear death. To hear this wasn’t surprising. Rather, it was his drawing from a religious image to say why that did impress me forever. After all, I thought we were all atheists here.

“Para mi, ustedes son mi cielo,” he said. Meaning it was his offspring that would remain of him post-departure, to become the life of his afterlife. He could have explained it rationally, by means of evolutionary biology, or, more aligned with his personality, in a jaded nihilistic way of “Nothing matters when you’re dead.” But no. He chose to relate his blood with heaven.

My blood warmed at the thought, as I looked up at a baby blue Texas sky, brushed by cool clouds, and the face of a fiery summer sun, which burned mine in waves, as the thought matured.

Among his children, each had their own interpretation of their father. Hearing him mentioned at the dinner table was like hearing different accounts of the same story. It was never the same man being discussed, attacked, or defended. Each had their own version of him, based on their own vision of him. It reminded me of how there are conflicting visions of God in different books, not to mention testaments, let alone in blood-relative religions. The deeper you go, the more complicated He gets.

The eldest son, growing up with the early, industrious version of his father, considered him tough but organized, generous with his gifts, yet withholding them too. This was the old man who had started a business and had loved his eldest as young fathers often do. In effect, becoming a balanced role model.

However, the middle children, who grew up with the successful version of their father, viewed their old man as opulent and extravagant, often living beyond his means. For his accumulation of debt, they never expected to receive much, nor did they ever take him too seriously, except to criticize his behavior.

Then there was the youngest, who the least spoke about his father. Also the one who never spoke to him at all. There was too much anger, which stemmed from having grown up with the financially ruined, decadent version of his old man: broad shoulders slumped, and his once imposing head held high just there to overshadow the few positive things left in him. This view of a devastated man in his third-act, had its roots in the busting of his business, the splintering of his home, leaving him no time to cuddle his baby boy. As a result, the youngest, if he ever did mention the father, did it tangentially, as if circumscribing the old man with poisonous jabs that touched upon the parts he hated, and nothing more. Never mentioning him directly.

All in all, the one common denominator among all the children — amid the mix of deference, apathy, pain, and aggression, lending their father his three dimension form — was this: a shared intense feeling of resentment towards their old man.

But, who am I but someone of blood, with his own point of view? I have read the Old and New Testament, have studied the conflicting accounts, but can see the parts that join them. Similarly I have listened to the stories of the older generation, have agreed or disagreed with their words, and discovered unnamed overlaps in their stories. These serve to frame my interpretation, work to build my vision. Yes there was pocketing of coins, yes there was slamming of tables at drunken dinners. In a word, the gentleman had been an ass.

Yet, were I able to interview his forebearers, I’m sure they would paint an altogether different image, of a square guy who studied engineering, and loved to sail. Of a child repeatedly abused by a boarding school priest, yet who on his seventieth birthday asked his wife to take him to church, not to pray, but to remember what it felt like to be young.

This was the man who turned my life on its head, and gave it, for a moment, his own meaning. His children would outlive him, just as I would outlive his children. When I have children of my own, they will outlive me, and so on. One great fairy tale after the other, circle of life upon circle of life, always beginning somewhere in the past and ending someplace after. Did I mention he was the one to tell me make believe stories while I was growing up? Now I want to tell stories. That’s my inheritance, my vision of him. Along with the aforementioned episode with the boat.

It was an optimist, the smallest Olympic sized boat, good for children and beginners. No frills, no unimportant rope line, not a pulley nor a curve purposeless. Just the barest of bare necessities. For its compactness and brevity of design, one must learn to harness everything about it — like learning to use a pocket calculator before moving on to more sophisticated tools. In return for this solid base, one may grow to become a shipping master.

Now I was out in the water, alone with my optimist, training, sailing, trimming sails and bronzing under the hot summer sun of many years past. The day was crystal clear, yet the water a mucky brown with mucous colored algae and floating debris, the kind water only folks from the Gulf can visualize without difficulty, or disgust. Add to this a maddening dehydration, and blistering palms, and you might begin to feel what I felt out there: like the king of the world.

After two hours of zigzagging, cutting across, going in circles, I drew closer to the docks, the entrance of which was indicated by two long piers pointing inward. It was time for lunch, I was hungry, and overhead the summer sun showed my skin no mercy. That same burning redness on my neck and back felt cool suddenly. The wind was picking up from behind. Luckily, I thought, the forward wind meant I could jibe full speed ahead, flapping my sail almost 180 degrees from one side of the boat to the other, as the invisible force at my back pushed.

Then, just as suddenly as the rise, the wind veered a dangerous three degrees in direction. It would have been unexpected, had I not felt the shift with my ears, as I had learned in sailing camp.

But then following events happened in quick succession, as fast as in a nightmare. I saw the full sail quickly deflate like a pinched tire, which I figured to jibe in the opposite direction, to take advantage of the change in wind direction, when lo and behold the wind shifted another few degrees further, causing the metal boom at the bottom of the sail to swing hard and fast towards my jaw. It snapped my face, and sent me overboard. Head first into the water, a flash of white as I crashed, and my leg must have knocked the tiller managing the direction of the ship off, because no sooner did I completely sink, did the small nimble boat topple over my body with a mighty splash.

I looked up, my eyes doused with the Gulf, my mouth full of it too. My ears, though, like tell tales, catching on to something, a voice.

From the man on the pier watching me.

He had been there the whole time, I would find out. Although I couldn’t see him, I was hearing him.

Because he shouted louder than the wind, sending his voice to where I was. Grab on to the boat! he said, in Spanish. I did, not easily, but I did, rubbing the sharp pain like battery acid under my mouth, guided only by his voice. Put your knee on the keel. Like that, like that! It’s the middle part of the boat, the piece that normally keeps the thing from toppling over the way it did. But now I applied my whole body weight to it, with a shiver despite the weather.

Slowly, but surely, the tip top of the mast swung up. The sail came up too, like the head of a shovel full of water, soon to flap in the wind.

I clambered up and over from starboard. And sailed the boat back to port, to home, under his watch and encouragement.

Handing me a towel, he put his hand on my shoulder. I looked up at him, the old man of my old man. One of the men who made the biggest impact on my life. Congratulating me, with words that said he believed in me, that he knew I knew, and was proud, he said, “Yo sabía, yo sabía.”

And we ate lunch together.