The problem with a 3/5-star movie is that you love it more than you hate it, but still that isn’t enough. You wonder the why and why nots over and over. By contrast, people who dish out 5’s like participation medals don’t want to hear how you didn’t like the movie as much as them; meanwhile folks who can’t give a Hollywood production anything over 2 probably couldn’t be bothered to stare at a cloud long enough to admire its silver lining or even dance in the rain. Whatever the case, have you noticed how both extremes want to recruit you?

Is there choice?

Barbie (2023): 3/5 stars

On Saturday, my wife and I got the chance to go to the movies, after leaving our eleven-month-old with his grandfather. Why it had to be him and not his grandmother, or why she had to leave the country on a mezcal retreat in Mexico with a secret cohort of women (or Wisconsin? she changes the story every time) or why I had imagined her doing more babysitting of her grandchild and less gallivanting, all may or may not have something to do with the point of Barbie. But I mention it to say I’ll spare you the details.

What I can say is that, at long last, baby-free, we could indulge in that aesthetic release couple often share when they outsource their parenting up the biological chain of command. We had no expectations walking in and we left not at all disappointed. The movie, we were pleased to discover, was not a movie, but a film: a satire of “entendres that are double,” a mordant critique of male stupidity, and an indictment of “Real World Patriarchy” as mean as the prettiest girl from your past who left you blue between your legs. All this to say, my wife welled up the last hour of the film. And of course I won’t say that I did too, during the exact same scenes. But we did leave the cinema feeling what we already knew. We should give our baby boy a baby sister, but like right now, before we pick him up, because girls rock too.

So, watch in good company, either with a really smart spouse who gets it, or a really dumb boy toy who won’t, or, as many of the people sitting around us did, as mother and daughter dressed in pink. More on this later.

Spoiler alert, rest of the post.

Speaking of audience, what caught my attention, more than the mothers and the daughters, was the concession stand server, a teen with “I heart Barbie” pinned to her head. When I asked “Did you like it?” she replied “I haven’t seen it.” No way! Was she lying? Maybe, if she loved it, she would disappoint me by raising my expectations. Maybe, if she hated it, she would ruin my good mood by speaking her mind. Or, just as likely, was she forced to wear the pin by a faceless corporate machine bent on dressing its employees for their own monetary gain via the feigning of the heart’s deepest emotion. Nah, I wasn’t sure, I didn’t care, and I was just asking to be polite because the pin caught my attention, although in retrospect it does make me wonder why a young girl would avoid watching Barbie, especially given the potential for a free flick between shifts. Little did I know that that level of avoidance, whatever the motivation — material or otherwise — is kind of what the movie is all about.

Or she prefers Oppenheimer.

1st star

The text is uncontestedly fantastic. By this I mean the one-liners, the dialogue, the monologues, and even the characterization plus overall plot. You shouldn’t expect less from the film’s writing duo: Greta Gerwig (Little Women, Lady Bird) and Noah Baumbach (Madagascar 3, The Squid and the Whale). From their filmography alone one admires their combined breadths of styles, from classic blockbuster to mommy-issues indie drama, as well as mastery of registers. For Stereotypical Barbie to discover her kindred spirit human in a vision or for Ken to give up his quest for patriarchal domination because “it isn’t about horses” are moments where plot, character, the mind, and the Word align like the planets in our solar system do when something magical is about to happen.

Now, if there were awkward product placements, mired beats for fans to admire vintage accessories, or even characters who came and went like the quick-draw of a boring date (thinking of the Chad in the cubicle, where did he end up?), we might safely blame these blips on rushed deadlines or too many chefs in the kitchen. An exec with too many ideas, say, or not enough funding. Nevertheless, the writer duo sneaks in more than a few punches, inserting that bit about the CFO opening the cash register on the Original Barbie concept after running the numbers; or, even better, the intertextual takes on 2001 (girls smashing doll heads in the beginning), Matrix (picking the high heels to keep things over the Birkenstocks to move forward with the journey), even Zoolander (Will Ferrel again as evil inventor, co-opoter of femininity, who insists on being called “mom”).

You could view these flares as unintended coincidences in an otherwise glossy rehash of the 1950s doll, but then you’d accidentally brand Barbie (2023) as derivative, or worse, not art . . . and miss the joke. It’s satire. Watch any Scary Movie. Let me call out just how brilliant those three steals are.

For example, 2001 is the quintessential “let me explain it” movie (which I love and would love to explain it to you) much to any Ken’s chagrin. Moreover, it proposes the female-less rebirth of the protagonist at the end (a real exhilarating climax to see the dude float through space, but, c’mon, why not at least clarify that the Star Gate sequence is really just traveling through a vaginal canal?). Where are the women here?? Next, Matrix, which, as an deeply serious film, is totally fair game for satire. The title itself is a co-opt of female genitalia, and its story tells of a Neo(nate?) who spends most of his life in the womb of a machine mother gone haywire, then proceeds to embark on an ass-kicking, black-leather, and synthetic-rubber hero’s journey. The only thing missing was for Trinity to be a Dominatrix, the story was so male. Last, Zoolander . . . a great pairing with Barbie, both thematically (discovering who you are and can be) and on a genre level (both are comedies). We already said the thing about Ferrel, but broadly speaking Gosling does don some Owen Wilson vibes with his Casa House, while Michael Cera . . . well, I’m not sure about Michael Cera.

My favorite parts, also, were text related: the two earth-shattering monologues delivered by the two mother characters. Again, more on this later.

2nd star

The new Barbie is bubble wrapped and tied with a frilly bow. How could it not be? Be that as it may, you’d be surprised how much the work has to offer men by way of life lessons. Heck, and if you don’t believe at first, just remember how much Dexter learned by stumbling into the wrong Convention.

It portrays an insecure Ken, who, granted, was designed to be no more than an accessory (like a car or a house) for Barbie. He lives and breathes for her (simp?) even when she doesn’t even love him back (simp!), doesn’t give him the time of day, nor the time of night for that matter. Fellas, don’t be a Ken, the script says.

And, the script continues, it’s actually cool to be a dude. I laughed hard watching Ken’s self-awakening montage in Los Angeles. Men break horses, men carve presidents into cliffs, and — palms in the air, bow down, you got me — men do rule the world. And even if the film’s stab at ‘people with a penis’ comes from some underlying resentment, hate, grief, embittered rage meant to bite us in the ass like a dog in heat, well hell, I gotta admit, the effect is just shy of a great rush of testosterone. I highly recommend it.

But don’t get too high, fellas. The next lesson is to not drag the fast food, the lite beer, and the muddy boots into your dream girl’s dream house. Don’t be a lazy do-nothing in her basement either. And certainly be weary of the stranger who, while you’re chilling with your lady, stands next to you all coy and plays on your instinct to eye-wonder at the napkin falling from her chest pocket to the floor. That new girl’s out to get ya, and in cahoots with other women too, according to the script.

Worse still and very cringy (I had to turn away from the screen) was that 4-hour musical number with the guitars. Your date might pretend to like it when you sing to her your favorite tune for the tenth time; but what she’s really doing is plotting your demise. She’s on her phone? She’s sits next to your best friend on the beach? Some new girl’s being extra sweet? Don’t pull a trigger, my guy, stay cool.

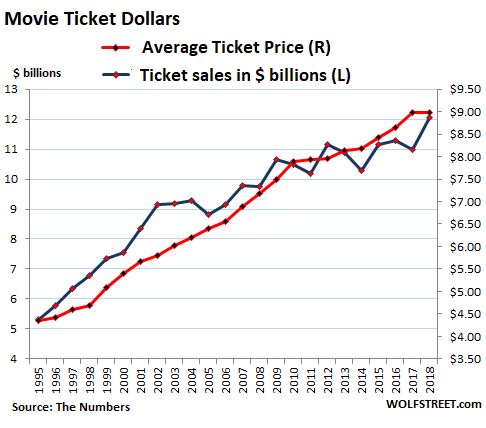

But I don’t blame you. I act like a Ken sometimes. Sometimes? I acted like a Ken almost straight out of the movie theater. Baby boy in tow, my wife and I drove to a dinner party later that evening. We were so eager to discuss Barbie with others who may have seen it. But no one had. So, for a good five, six minutes, I vainly explained my thoughts on it, even while I saw people turn away to pet a dog or my taste in cinema got seriously questioned. Despite all “consciousness of my self” (which I knightly endured!) I do hope to have inspired my beloved tribesmen and women to spend $50 bucks-ish on a pair of matinee tickets, parking and popcorn. Maybe I inspire you too?

3rd and last star

My last star goes to the film for its ability to dredge up an old yet beautiful myth, as sneakily as a magician pulls a bunny out of a hat while his assistant pulls your wallet out of your pocket, in what would seem to be a story about female empowerment but really is the tragedy of a mother’s failure to protect her daughter against the allure of Death himself.

Stated more plainly, Barbie borrows heavily from the Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone: the OG mother-daughter tale. It borrows so heavily in fact, that one is able to see the second set of footprints, whenever this new story veers off its originator’s tried and true path.

Recall, Demeter is the goddess of fertility. She puts the seeds in the fruit; she puts the milk in the breasts; she blankets the earth in an eternal spring. A total Barbieland for her and her offspring, including Persephone, her innocent tween daughter.

On day Persephone turns thirteen and decides to go flower picking inside a beautiful forest glade. The birds are singing. The sun is shining. And her mother is nowhere around.

Finally alone, Persephone catches sight of a particularly pretty flower over yonder; she skips to go pluck it. Boom! The earth floor tears opens. And out from the gash rides Hades, King of the Underworld. He has been watching this little bud and has been waiting to pluck her himself at the ripe, childbearing age of thirteen, so that he may take her for his bride, as well as in other ways.

Now, Demeter, poor mother, she can’t find her daughter anywhere. No one has seen her, not the nymphs, not the Olympians. In her desperation she breaks down, gets depressed, is crippled by thoughts of inadequacy and early-onset dementia. She can’t even remember to take care of the earth! Plants stop bearing fruit. Breasts stop producing milk. And the once-eternal spring withers in to a long, dead winter. Wood cannot even be used for fire. And the snow never melts into water. No one is happy, to say the least. Not even the gods who live forever, because what’s the point of immortality, if there are no summers to make love in, nor autumns of which to celebrate?

In the version of the story told to me by my sixth-grade English teacher, it is the Olympians who take pity and send the messenger Hermes to talk with Hades. The King isn’t so willing to lose his new bride; he does love her to death (pun intended); and low-key Persephone also enjoys not having a helicopter mom and plans to kick it forever in the Underworld as Queen.

But . . . I like the version I read recently in Women who Run with the Wolves. There is no Deus ex machina solution here, no gods intervening for other gods in the nick of time or when they feel like it. No, Demeter investigates the case of her missing daughter. She asks for her high and low. And eventually she meets a goddess. Her name is Baubo. She has no head, uses her nipples for eyes, and has a mouth between her legs. Again, a real goddess, Baubo. (She should have been in the movie, imho; how hard is it to rip a Barbie head off a doll?)

First, mythical Baubo soothes the grieving mother by telling her some dirty jokes and making her laugh deep within her belly. Next, she guides the mother to Hades. And there, the two of them are able to rescue Persephone from the underworld.

Remember, though, that Demeter isn’t able to pull her daughter away from Hades completely. Persephone either fell in love with her new daddy Hades, or she just enjoys the throne in and of itself. There’s also that pesky trick Hades plays on her. Hades tells Persephone she can go out to join her mother Demeter, “But wait! Have these pomegranate seeds as a road-trip snack.” Little did his bride know that, according to Ancient Greek Tradition, to eat the food of your captor guaranteed your return. On her wait out with Demeter and Baubo (or Hermes, depending) Persephone eats six of those bloody seeds, thus ensuring that six months of every year she had to return to the Underworld. Thus we have the cycles of life and death on earth: the blossoming of spring is when Demeter happily blesses the earth alongside her daughter, while the hibernation of winter reminds people on earth that it’s time to wait out the cold in one another’s arms, because Persephone and Hades have the “do not disturb” tie on the doorknob, and Demeter ain’t coming around to fertilize nothing.

I like the Baubo version of the story, because it gives us a more female-agented edge to an already female-forward story, but also because it’s a reminder to the wise that girls who live long enough to bleed might just turn into little dark goth kids who want to shut themselves in with an Underworld King, avoiding the great responsibility that comes with the great power to channel life and death between their legs. But hey, if a mother really, really wants to, and remembers that her nipples can also see and that between her legs there is an oral tradition to be passed on, then she can at least rescue half of her daughter. It’s a nice story. A godly compromise.

Anyway, most of this I saw in Barbie. You can connect the dots. Except where the two stories don’t connect.

Missing 2 stars ;(;(

In true Hollywood fashion, the film packs two stories for the price of one. But in a step removed from the classic formula of “a story within a story,” Barbie has the two stories run parallel to one another. I didn’t think it worked so good.

There is the background Demeter-Persephone pairing of the “Real World” mother-daughter; and the foreground Demeter-Persephone pairing of the “Barbieland” creator Ruth Handler (inventor of Barbie) with Margot Robbie as Stereotypical Barbie. These two worlds intertwine when a “Real World” little girl plays with a “Barbieland” Barbie. The little girl projects her hopes and dreams onto her plastic doll, and the plastic doll lives out a perfect existence in the fantasy realm, where, again, a woman can succeed at anything by being a woman alone. Kind of complicated, but let’s roll.

The plot twist we learn about is that this connection between the two worlds can spell havoc for one world or the other, should something go wrong. For example, if a girl abuses her barbie, then the parallel in Barbieland becomes a “Weird Barbie.” What’s interesting about this film is that the havoc is caused when the Mother character starts playing with her Daughter’s Barbie. The adult (Demeter), trying to act like a little girl (Persephone), abusing the natural order of things by projecting her crippling anxiety, cellulite, and death ideation onto poor Stereotypical Barbie. But, this analysis is as far as the script was willing to go; I wish I had gone deeper.

Worse, there is no Hades character tearing apart the fabric of space-time to steal Persephone, rather it is the Mother who does this. And she does it because of her dead-end (underworld? soul-crushing?) job is itself an extension of the “Patriarchy.” That’s supposed to be our Hades? The abstract representation of “men run the world and crush women at every turn” which has become a household vocab word, despite much apprehension about its spelling?

According to the film, anyway, the new Hades is the “Patriarchy.” Or it’s Will Ferrel? The Mother does play secretary to the CEO of Mattel, which I guess is being trapped. In any case, the “Real World” makes daughters hate their mothers, turns “weak men” in to women, and makes everyone cry. Pretty Hades-esque.

Blah. Just not enough DEATH, what can I say, especially for a film that explicitly centers existential angst in its opening dance number “Sometimes I think about death.”

A missed opportunity for Barbie, and Margot Robbie, more than just cellulite and flat feet. But the realization that she must break the eternal spring of Barbieland by loving her pregnant neighbor and perhaps asking her gyno at the end for more than just proof of her human femininity. Maybe she can ask for some condoms.

And get extras too for Mom. That way Dad can learn some useful Spanish. In the bedroom.

Sure, on the one hand, you have Kens that are first silly and a bit bland and then transform into full-on chauvinists. And on the other, you have the all-male board of Mattel, composed mostly of bumbling idiots and led by an even bigger idiot CEO.

Then, there’s Allan.

And while he’s supposed to be Ken’s buddy, his behavior doesn’t mirror that of Kens at all.

Instead, he’s charming, funny and warm, albeit a bit awkward. He isn’t ravaged by the same feelings of insecurity Kens seems to be. Nor does he seek constant validation, affection and approval from Barbies.

He’s also one of a kind, literally, as there’s only one of him.

Even when Beach Ken brings patriarchy to Barbie Land, Allan doesn’t join his quest of turning it into Kendom. Actually, he tries to escape it as he doesn’t want to fit into the world of caveman-like masculinity.

But despite not appearing particularly strong or masculine, he takes on the protector role and gets into a fight with several construction Kens, beating them up in defense of the mom and daughter

Yup, Allan is an actual good guy.

He represents a healthy brand of masculinity and who men could be if they wouldn’t give in to the pressures of a patriarchal society that tries so hard to convince them they’re weak and worthless unless they act like brutish dominators.

I also see parts of him in the men around me — including my boyfriend and brother. Just like Allan, they don’t exactly fit in. They’re the odd men out.

And on several occasions, they’ve been told by other men — and women — that they should just ‘man up.’

So, no — Barbie movie is hardly ‘anti-men.’ It isn’t anything like the prettiest girl being “mean” and leaving your balls blue. Just no.

It’s simply anti-patriarchy and a specific form of masculinity — the one that doesn’t only bring harm to society but men as well.

What Gerwig did was simply hold up a mirror to our society. Kens in the movie are treated just as women are treated still today.

Because if that wasn’t the case, I really doubt we would see as many men foaming at the mouth with rage as soon as it was released as we have.

of course, if you’re a man who fails to see how the movie flips the script or refuses to acknowledge our society’s treatment of women or both, seeing YOURSELF represented as the silly, incompetent and largely inadequate Ken character doesn’t feel great or perhaps it is “cringy.”

The kens weren’t treated even half as badly as men have shown they are capable of treating women. Men are so quick to treat women like nothing. An after-thought. And yes, an accessory.

Serious insight, Lola, thank you. I respect the time you took to unpack the Allan figure in your comment. In my reflection, I just mention him in passing; so I appreciate you stopping to out his value (even to the Allan figures in rl). Maybe there’s a connection b/w him and the father character learning Spanish . . . but we’d have to ponder it deeper. Just a twinkle of a thought.

As an aside, I am not sure if you are saying I was “cringe” when I compared myself as Ken. If so, sorry not sorry lol. This post has been pretty cringe for a lot of people lately who have brought up to me its various points in various conversations. Each time someone brings up how the piece made them feel it has, naturally enough, helped me grow as a person.

In any case, your point about flipping the script was not (not!) lost on me; sadly it was lost on the people who only saw the trailer. (Hence my desire to write about the movie, so more people go see it.) There’s that powerful line in the movie, spoken by the forgotten cubicle character, saying something to the effect of, “And I’m a man who no men listen to; I guess that makes me a woman.” Now that’s world-class cringe.

At least men and women in rl can work together, like the two writers of this script, to produce something fabulous: A human movie. A human doll. A human life.